See the buildings which won the awards (PDF 7.5MB)

Awards Speech

Thank you, David for those kind words, I’m delighted to be here and share this awards ceremony with you.

Thank you, David for those kind words, I’m delighted to be here and share this awards ceremony with you.

Now, I know how affectionate you all feel towards architects and how in touch you think we are with the real world, but I think you’ll be surprised to find how much common ground we have.

I was of course delighted to be asked to help judge these Triennial Awards, because craftsmanship is something I care a lot about. And let’s face it, the winners of these awards are in very distinguished company indeed - Sir Giles Gilbert Scott got one for the glorious brick cathedral that is Battersea Power Station.

The judging experience itself was slightly surreal, admittedly. You have to admire the sheer ambition of an organisation that draws up an itinerary to inspect a dozen London buildings – including one on the notoriously hard to access Olympic site – to coincide with both the Chelsea Flower Show and the state visit of the President of the United States. But even without a posse of police outriders, all went well until we got to the Reform Club on Pall Mall, where we were to check out the splendid new roof.

Not without a tie, though. The neckwear police on the door were adamant. Grade 1 listed, you see - it’s all about standards, and standards are by their very nature inflexible. So, kitted out in a rather fetching Paisley number they keep for the purpose (but no safety helmet) I eventually made my way to the top.

Safety helmet? Sumptuous as the new Italianate tiling undoubtedly was, I wouldn’t have ventured out onto that exposed, railingless steel walkway with anything less than a parachute. I know your motto is In God Is All Our Trust, but on a very wet blustery day, that seemed to be pushing the limits of faith a bit far…

All in all though, I found the judging to be a fascinating experience, with an impressively diverse display of technical skills, elegantly applied.

At a time when many people struggle to assemble an IKEA flat pack, craftsmanship is a woefully overlooked virtue. But true craftsmanship goes beyond functional excellence – there’s something profoundly satisfying about a thing that’s supremely well done, and it’s a satisfaction that lasts. Fine craftsmanship connects you to the actual process of making. It gives you a sense of the skill, time and painstaking effort that goes into making something look effortlessly perfect.

Craftsmanship is part of the reason I became an architect in the first place, because for as long as I can remember I’ve enjoyed building things. My Dad was a DIY fanatic, and I vividly recall as a child helping him to build a garden shed for us to play in.

In retrospect, it was an early lesson in the use of the correct materials, because Dad chose to build his new shed out of a superbly versatile natural material that human beings have been using in construction for more or less 4,500 years. A material prized for its stability and excellent insulation properties. A material that comes from the earth itself. That’s right: asbestos!

And that’s when I first learned the value of working closely with whoever was actually doing the construction, and why I’ve never understood some architects’ aloofness towards the rest of the industry. Being on site or in the factory with those who have the skills to physically make things is part of the job I really enjoy.

Sitting in judgement on other people’s work is a different matter, though. Being a judge of this competition felt a bit like being one of the searchers the Company used to appoint to inspect your members’ work.

As a searcher, of course, you had the power to fine miscreants - mostly for using indecent language as far as I can make out. No change there, then.

Hefty fines were also imposed on the tilemakers of Havering, who according to the records “were not above digging up the public highway to get the raw materials they needed.” Still, that’s Essex for you.

And at one guild dinner, one Richard Mason, having refused to drink the loving cup after the newly elected Master, excused himself by saying he thought the Master had smallpox, for which calumny he was fined 4 shillings. I’m pleased to see that the current Master seems to be in rude health, and that things have changed quite a lot since those days – especially in the last decade or so, which is what I want to talk to you about today.

The point is, major change often happens more quickly than anyone expects. This very guild lost its monopoly over bricklaying in London after the Great Fire, of course; when the King decreed that all homes should henceforth be built of brick or stone instead of timber, there was simply too much rebuilding to be done, so they had to allow craftsmen from elsewhere. The thinking and methods of the entire industry changed overnight.

In a sense, what we’re seeing today is a shift of this magnitude, away from the glass box and towards more environmentally benign materials and ways of building. And that shift promises great opportunities for all of us in this room. I’m not saying that from now on we’ll all be designing buildings of brick and tile, but that the skills and technologies you represent have an important place in the only possible architectural future, which is a sustainable one.

As I see it, we’re faced with three main threats to our prosperity. The first is the economic cycle. The events of the last couple of years prove that despite all political claims to the contrary, we have little control over the never-ending dance of boom and bust, which has itself largely been driven by lending against inflated property values. And as the unfolding situation in Greece frighteningly demonstrates, the financial glue holding everything together in our interconnected world can come horribly unstuck very quickly indeed, with consequences no one can accurately predict or plan for.

The second threat comes from hidebound, backward-looking attitudes that resist change per se. As some of you may know, I’ve been involved recently in a controversial project to redevelop part of Broadgate to build an environmentally sound new 700,000 sq.ft 21st century headquarters for the Swiss investment bank UBS.

A few weeks ago, the Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport eventually rejected the application by English Heritage and other conservationist groups to have the existing 1980s buildings listed. By doing so, he sent out a clear message to the world that the UK is open for business; in order to remain internationally competitive, the City must be allowed to adapt to meet the long-term business needs of current and future occupiers, which our new building does. As our way of life changes, so must our buildings.

There’s always been a tension between the old and the new, and it’s true to say that the not-very-old is most vulnerable to replacement by the new because it’s only with the passage of time – and a long time, at that – that the true cultural value of any artefact as a symbol of its age becomes apparent.

As I understand it, although its incorporation by Royal Charter came later, this organisation is only five years away from its 600th anniversary. 600 years! And with that kind of perspective, I’m sure you’ll agree with me that as soon as we stop innovating, we might as well pack up and go home.

London isn’t like Florence or Venice, perfectly preserved at a golden moment in time. Total conservation is fine for cities whose wealth is generated almost exclusively by tourism, but London’s not like that. As the cultural and financial engine of the nation and a leading world city, London is by its very nature dynamic - and dynamism is about embracing change. Not just accepting change, but pushing it as far as it will go.

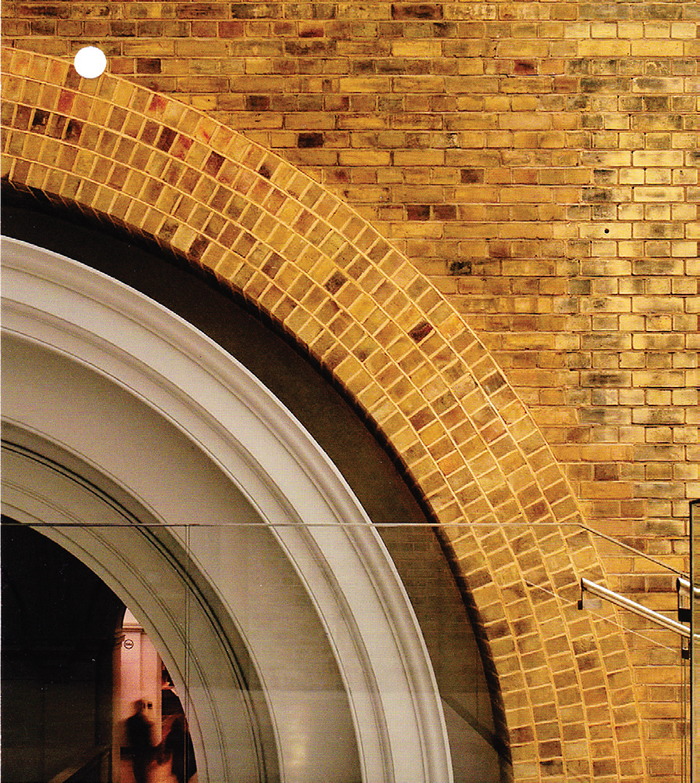

Don’t get me wrong - I’m not saying “out with the old and in with the new” for the sake of it. We’ve just recently seen St Paul’s without scaffolding for the first time in 15 years, and delightful it is too. The new palazzo-style imbrex-and-tegula clay tile roof on the Reform Club I mentioned earlier was directly inspired by Charles Barry’s original watercolour of the proposed building, and the result looks terrific.

Or take another entrant, the Olympic Park electrical substation, where the striking use of dark brick reflects the traditional dark stock on the former industrial buildings on the site – which, incidentally, were re-used in crushed down form in the new building. The ‘brown roof’ of crushed materials is designed to encourage local wildlife species to colonise naturally.

So the way to resolve this tension between the old and the new is emphatically not to fall back on simply replicating the old. Although your instinct might be to welcome traditionalist tendencies on the grounds that it provides gainful employment for lots of worshipful bricklayers and tilers, but Disney-like pastiche takes us back to a past that no longer exists. It’s a dead end. The way forward – the only way forward - is to design for sustainability.

And that of course brings me to the biggest threat to our prosperity of all: dealing with man-made climate change.

On that score, our new age of austerity may actually have helped. When times are tough, we as an industry tend to work more closely together in order to improve efficiency and cut costs and waste. The same is true on the design front. Before 2008, many projects sought to outdo each other with the complexity of their shapes.

No more. We find ourselves in a new era of exploration to find a new paradigm for a new post-recession architecture - a paradigm that has the challenges of climate change at its heart.

The effects of climate change are already plain to see, all around us. We’re in between kicking our addiction to fossil fuels and embracing the next generation of renewable power sources. And remember, we’re the ones who make the buildings that currently account for 70% of human CO2 emissions. 70%! Not gas-guzzling Chelsea tractors or long haul 747s, but buildings. As such, we all have a moral duty to respond by innovating low carbon, low energy solutions.

The next generation will look back on the last few decades and think ‘what on earth were they thinking of?’ How could they have been so profligate? Why did they think they could burn so much energy with no consequence?

Even the building that may go down as the symbol of the era as far as London goes - 30 St Mary Axe, the Gherkin, which some say I had a hand in - has the same cladding performance all the way round. Why isn’t it responsive to the way it faces?

Strange as it may seem now, it simply never came up at the time. We’re only talking about a dozen or so years ago. The world changes faster than you think.

At Make we wouldn't even contemplate putting glass all the way round today; we’d use higher performance materials to keep the solar gain down. We’ve changed because the world has.

It seems blindingly obvious to me, that buildings need to relate to their location and their climate. And for buildings in the UK, that means we need to end our love affair with transparency.

Lightweight buildings with their hermetic curtain walls and massive reliance on mechanical systems make no sense today. The office buildings of the recent past are like submarines - if the power goes off, everyone dies.

And so, as I’m sure you’ll be sorry to hear, the glass binge is over! We simply can’t carry on designing in the same old way, with fully glazed buildings where the facade has to be really complicated with all sorts of intricate shading devices, ventilated cavities and opening slots, then adding an extra layer of glass to avoid the shading getting dirty. And to add insult to injury, the end result gets described as ‘low energy’ when an insulated brick wall with punched windows would have beaten it hands down on the energy saving stakes, let alone wiped the floor with it on cost grounds!

That’s why at Make, we’ve been campaigning for the death of the glass box. To us, it seems obvious - but the resistance from some of our contemporaries has been fierce. We do, however, passionately believe in the need for a new architecture, and as fellow members of the team who make buildings, we should be working together to develop new answers to these challenges. We want to help develop completely different kinds of building that chime with the low carbon imperative.

I believe we’re at a defining moment in this industry, and we need to take low carbon right into the heart of the design process. If we don’t achieve zero carbon buildings, the next generation will curse us for it, and rightly so.

What I’ve seen in the process of judging this competition and talking to some of you here has been very encouraging. I’ve seen materials used in new ways – materials that have an important role to play in low carbon construction. And the standard of craftsmanship I’ve seen has been no less than inspirational.

Personally, I want to create the best buildings in the world. I want to help save the planet, too. And the best way to do both is for us to work together as an industry, to combine our expertise to devise a new type of low energy architecture that’s simpler to build, fantastic to look at and delightful to be in.

Thank you.

Floor Tiling Award

Roof Tiling Award

High Commendation for Brickwork